At the end of October, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell announced a 25-basis point (bp) cut to interest rates, following a 25bp cut in September. This was the second cut of 2025, with another meeting scheduled in December. According to Powell, further cuts in December are “far from” a foregone conclusion.

The Federal Open Market Committee meets to determine the interest rate level that helps achieve their dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability. Among the many tools the Fed has, interest rate changes are among its most potent. Even though the interest rate adjustments receive regular news coverage, it can be confusing to understand what it means in relation to the many other types of interest rates an individual may encounter.

Whenever the Fed discusses setting interest rates, they are referring to the “federal funds rate.” According to the Fed, “the federal funds rate is the interest rate at which depository institutions trade federal funds (balances held at Federal Reserve Banks) with each other overnight. When a depository institution has surplus balances in its reserve account, it lends to other banks in need of larger balances. In simpler terms, a bank with excess cash, which is often referred to as liquidity, will lend to another bank that needs to quickly raise liquidity.”

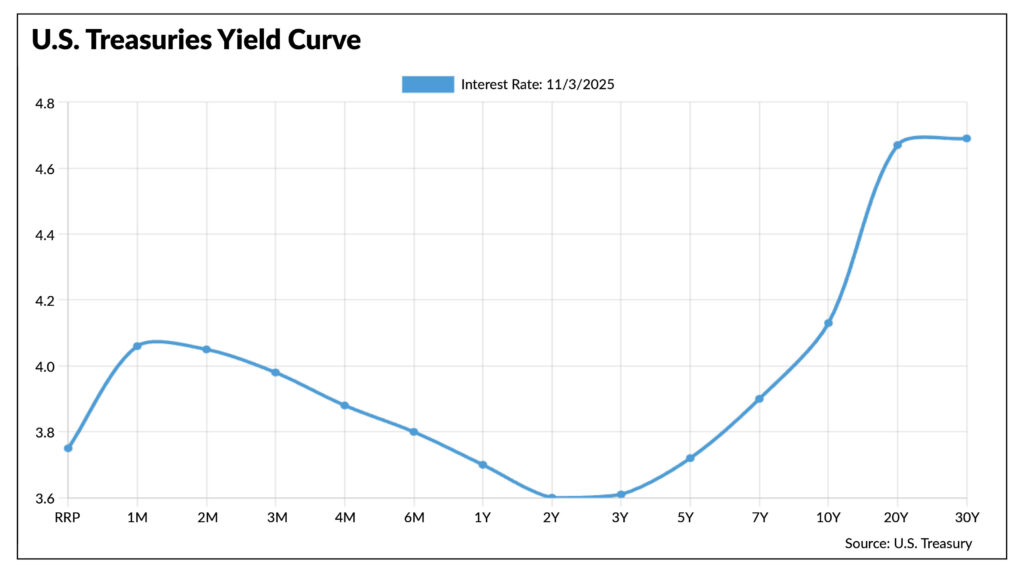

The Fed Funds Rate reflects this overnight, short-term rate designed to provide banks more liquidity to meet various capital requirements and regulations to protect consumers. This rate is typically stated in an annualized-term and is currently set at 3.75 – 4.00%. This often reflects the short-term interest rate that banks and investors earn on federal government backed lending. Given that the U.S. federal government can print money to meet these obligations, this rate is viewed as risk-free. These rates also have an immediate impact on short-term instruments like money market funds and CD rates. Government rates for bonds greater than one year are typically higher, reflecting a “term premium,” or increased compensation for longer-term lenders due to more uncertainty that comes with longer obligations. This creates a traditional upward sloping yield curve, reflecting all the interest rates available across U.S. government bonds over various maturities.

The Fed can only set the short-term rate, whereas longer-term rates on government bonds are driven by markets and impacted by factors such as fiscal health, inflation, unemployment, GDP growth, government stability, and more. These factors can influence what investors are willing to lend at various time frames, and, along with the overall bond supply and demand dynamics, will shape the yield curve. While the Fed can set the short-term rates, these broader considerations can run counter to short-term Fed intervention, helping explain how the yield curve can twist and distort over time.

The rates on the yield curve reflect guaranteed U.S. government bonds. However, they also influence other more familiar rates such as auto loans or home mortgages, which can vary depending on who the borrower is.

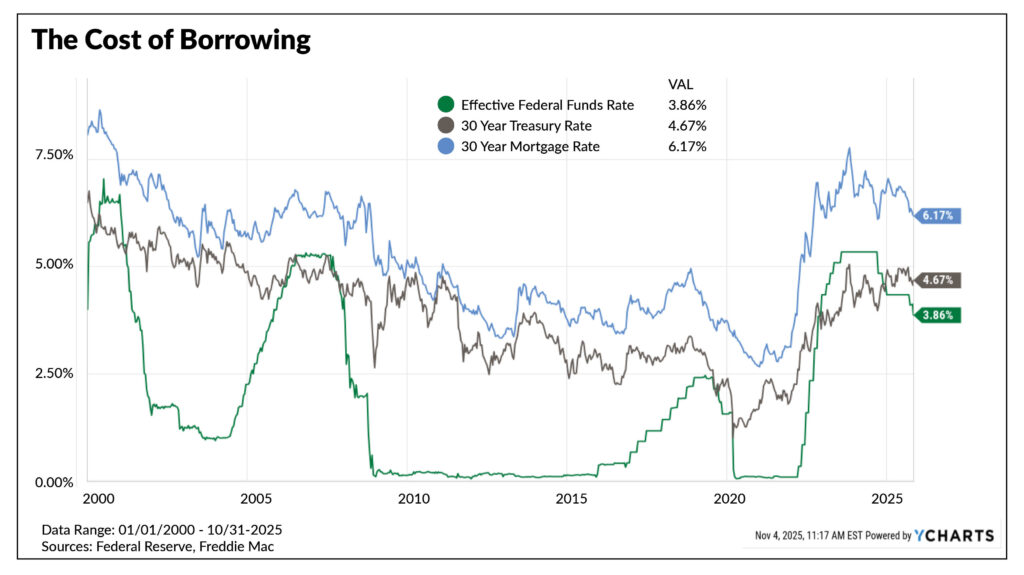

While the U.S. government can always print money to meet its obligations, corporations and individuals cannot. This difference from a 30-year U.S. Treasury Bond and a 30-year mortgage rate comes down to the borrower and their ability to pay. Currently, a U.S. Treasury Bond is yielding ~4.7%, whereas an average 30-year mortgage rate for high credit rated individuals is ~6.2%. This 1.5% difference shows the contrast in perceived risk between lending to the U.S. government versus lending to a homebuyer—highlighting the government’s assumed stronger ability to repay.

As the chart shows, these two rates typically move in the same direction, but can become closer or further apart based on the overall economic environment. Typically, when the economy is healthy, the difference narrows as investors and banks are more comfortable that their long-term obligations will be met. In more challenging periods, this “credit spread” can widen to reflect greater uncertainty over an individual’s ability to repay.

The Fed adjusting interest rates can have many impacts to individuals, corporations, and overall stock and bond markets. How these short-term rates influence longer-term rates for both government bonds and other debt instruments like mortgage rates can vary based on the economic environment. When it comes to financial planning, having a good understanding of the factors that can impact interest rates over time is a valuable building block to successful long-term financial results.

As always, if you have any questions, please talk to your JNBA Advisory Team.

Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this blog serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from JNBA Financial Advisors, LLC.

Please see important disclosure information at jnba.com/disclosure